Become a Patron!

Excerpted From: Kelly Lytle Hernández, Mae Ngai, and Ingrid Eagly , United States of America, Petitioner, v. Refugio PALOMAR-SANTIAGO. No. 20-437. (March 2021), Brief for Professors Kelly Lytle Hernández, Mae Ngai, and Ingrid Eagly as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondent, 2021 WL 1298527 (U.S.) (Appellate Brief), Supreme Court of the United States. (Footnotes) (Full Document)

To claim that the Undesirable Aliens Act of 1929 (8 U.S.C. 1326 ) was founded in anything but deep-seated racial animus is to ignore the words spoken on the Congressional floor in the 1920s that led to its passage. The congressional debates made clear that legislators saw Mexican immigrants as a “social problem” to be controlled because they were a threat to white hegemony. This perceived threat was the animating motivation behind the eventual passage of the Act and, in particular, the criminal entry and reentry provisions.

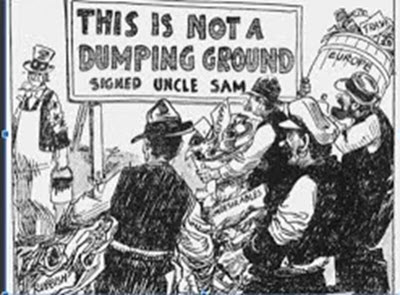

A. A “Nativist” Political Coalition Advocated Severe Restrictions On Non-White Immigration In The 1920s

The felony unauthorized reentry after deportation statute codified at 8 U.S.C. 1326, like its misdemeanor counterpart, codified in Section 1325, traces its origins to the 1920s. That era saw increasingly vocal and active white resentment of other racial groups, a period so racially fractious that it earned the moniker the “Tribal Twenties.” Kelly Lytle Hernández, City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles, 1771-1965, at 131 (2017) (City of Inmates) (citing *6 John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925, at 264-299 (1988)). This was “a time when the Ku Klux Klan was reborn, Jim Crow came of age, and public intellectuals preached the science of eugenics.” Ibid.

Over the course of the decade, a group of white lawmakers known as the “Nativists” increased their political influence by pushing an agenda that demonized all immigrants from anywhere other than certain favored European countries. City of Inmates 131. The Nativists warned that freely permitting the inflow of immigrants from around the world would repeat the “tragedy” of the slave trade, though ironically the Nativists used the word “tragedy” to refer not to the evils of slavery but rather to the introduction of African people into the United Sates. Ibid.

Meanwhile, Mexican immigrant laborers were making a home for themselves in borderlands and building a “MexAmerica.” City of Inmates 131-132. These immigrants settled into and created communities, built homes and “established everything from newspapers and businesses to bands and baseball teams.” Id. at 132. They “made full and permanent lives for themselves and their children-an increasing number of whom were U.S.-born citizens-in the United States.” Ibid. The Nativist movement saw these burgeoning communities as a threat to its national project of restricting permanent immigration to select Europeans. Id. at 134 (discussing how the boom in Mexican immigration “unnerved the Nativists” as it “threatened to degrade the nation's ‘Aryan’ stock”).

*7 B. The National Origins Act Of 1924 Failed To Fully Achieve The Nativists' Anti-Mexican Goals

Faced with the prospect of non-white immigrants settling in the United States, the Nativists resorted to incremental legislative efforts to influence the composition of the immigrant pool according to their racist view of what was desirable. The Nativists secured an early, if partial, legislative victory with Congress's enactment of the National Origins Act of 1924 (“1924 Act”). Pub. L. No. 68-139, 43 Stat. 153. That law banned all Asian immigrants and required other immigrants who were potentially eligible for entry to submit to inspection at a U.S. immigration station. During inspection, aspiring immigrants would take a literacy test and a health exam, and pay $18 in head taxes and visa fees before being granted entryall requirements that the Nativists believed only certain Europeans could pass. City of Inmates 132-133. The 1924 Act also established a system of national quotas limiting the total number of immigrants allowed entry from eastern-hemisphere countries each year; of the total annual quota allotment, 96% was reserved for European immigrants. Id. at 133.

While these restrictions on immigration from outside Europe were remarkably stringent, the Nativists had actually been pushing for even greater restrictions on non-European immigration. However, they were stymied by business opposition from representatives from the Western states, which increasingly relied on the Mexican immigrant workforce. Due to “the decline of white male itinerancy, the exclusion of Chinese workers, and the nadir of California's indigenous population,” Mexican immigrants had emerged as a significant proportion of the low-wage workforce in the region. City of Inmates 132. As the President of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce put *8 it, “[w]e are totally dependent ... upon Mexico for agricultural and industrial common or casual labor. It is our only source of supply.” Id. at 131 (quoting Devra Weber, Dark Sweat, White Gold: California Farm Workers, Cotton, and the New Deal 35 (1994)). Speaking on behalf of himself and various livestock raisers' associations, rancher Fred Bixby testified before the Senate Committee on Immigration about industrial reliance on Mexican labor. He noted that in California “we have no Chinamen, we have not the Japs. The Hindu is worthless; the Filipino is nothing, and the white man will not do the work.” Kelly Lytle Hernández, Migra! A History of the U.S. Border Patrol 30 (2010) (Migra!) (quoting Restriction of Western Hemisphere Immigration: Hearings on S. 1296, S. 1437, and S. 3019 Before the Senate Comm. on Immigration, 70th Cong., 1st Sess. 24, 26 (1928) (statement of Fred Bixby)).

At the time, immigration authorities counted approximately 100,000 Mexicans crossing the border each year. The Nativists' proposed quota would have limited entries to a few hundred. City of Inmates 134. Thus, agribusiness opposed any quota system simply because they relied on Mexican laborers.

Because the bloc of pro-business representatives opposed the quota, the Nativists were forced to choose between a Mexican exemption to the quota system and no immigration quotas at all. They chose the former. The law ultimately exempted from the quota all immigrants from the Western hemisphere, whereas all other nations had a combined annual limit of 165,000 immigrants. City of Inmates 133; John M. Murrin et al., Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People, Volume 2: *9 Since 1863, at 659 (7th ed. 2015) (Liberty, Equality, Power). $%^2

The Nativists remained unsatisfied over the following years. Congressman John C. Box, who would later cosponsor a 1926 bill that would have limited Mexican immigration, opined that “[t]he continuance of a desirable character of citizenship * * * will be violated by increasing the Mexican population of the country.” Migra! 28 (quoting Seasonal Agricultural Laborers from Mexico: Hearings Before the House Comm. on Immigration and Naturalization, 69th Cong., 1st Sess. 124 (1926) (statement of John C. Box)). During the congressional hearings for the 1924 Act, another Congressman questioned the wisdom of exempting the Western hemisphere from the nation-by-nation quota system by asking “[w]hat is the use of closing the front door to keep out undesirables from Europe when you permit Mexicans to come in here by the back door by the thousands and thousands?” Id. (quoting David Gutiérrez, Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity 53-54 (1995)).

With the Western hemisphere not subject to the quota system, Mexicans continued to immigrate in greater numbers. By the end of the 1920s, Mexico became one of the leading sources of immigration to the United States. Migra! 28. But the Nativist backlash continued to build, leading to what would become the Undesirable Aliens Act of 1929.

*10 C. Post-1924 Congressional Debates Over Mexican Immigration Policy Reveal Widespread Racism Against Mexicans

The 1924 Act's foundational compromise did not last long. Congress considered bills designed to curtail Mexican immigration in 1926 and 1928. And although these debates ostensibly pitted Nativists against agribusiness lobbyists, legislators from both groups used openly racist language when describing Mexican immigrants.

The Nativists voiced their usual fears about the effects of the United States' shifting demographic composition due to immigration. For example, the Immigration Restriction League warned the Senate that “[o]ur great Southwest is rapidly creating for itself a new racial problem, as our old South did when it imported slave labor from Africa.” Migra! 29 (quoting Restriction of Western Hemisphere Immigration: Hearings on S.1296, S.1437, and S. 3019 Before the Senate Comm. on Immigration, 70th Cong., 1st Sess. 188 (1928) (statement on Mexican immigration submitted by the Immigration Restriction League)).

While the Southwestern agricultural lobby fought against proposals to curtail Mexican immigration, they accepted the racist premise underlying the Nativists' worldview. In 1926, an agribusiness lobbyist named S. Parker Frisselle testified before Congress that “[w]e, gentlemen * * * are just as anxious as you are not to build the civilization of California or any other Western district upon a Mexican foundation.” City of Inmates 135 (quoting Seasonal Agricultural Laborers from Mexico: Hearing on H.R. 6741, H.R. 7559, and H.R. 9036 Before the House Comm. on Immigration and Naturalization, 69th Cong., 1st Sess. 7 (1926) (statement of S. Parker Frisselle) (Frisselle Testimony)). “With the Mexican comes a social problem.... It is a serious one. It comes into our schools, *11 it comes into our cities, and it comes into our whole civilization in California.” Migra! 29 (quoting Frisselle Testimony at 6-7).

Agribusiness disagreed with the Nativists on the question of whether Mexican immigrants were here to stay. The southwestern lobbyists believed that the Mexican migrant is more like a “pigeon,” who “goes home to roost” at the end of each season. City of Inmates 135 (quoting Frisselle Testimony at 6, 10, 14); see also id. at 136 (quoting George Clements, “Mexican Indian or Porto Rican Indian Casual Labor?,” folder 1, box 62, GPCP (Clements Testimony) (“A Mexican would not settle in the United States because ‘his homing instincts take him back to Mexico.’ ”)). Even if they were wrong on this point, and the Mexicans stayed, Mexicans could easily be deported if need be, as agribusiness lobbyist George Clements testified in 1928. Id. at 135-136 (citing Clements Testimony).

Agribusiness also fought racial animus with more racial animus, raising the specter of Black workers from Puerto Rico who might serve their labor needs if Mexicans could not. As Clements warned, “[t]he one problem which should give us pause is the negro problem.” City of Inmates 136 (quoting Clements Testimony). He went on to explain that if Mexicans were denied entry into the United States, the “[Puerto Rican] negro will come.” Ibid. Clements thus forced Nativists to choose between “Mexico's deportable birds of passage or Puerto Rican Negroes, who, as citizens, would leave the edge of the U.S. empire to settle within the final frontier of Anglo America.” Id. (citing Clements Testimony).

While the two camps had their differences, the congressional debates of 1926 and 1928 make clear that both Nativists and agribusiness industrialists agreed that Mexican immigration presented a “social problem” that had to be managed. A businessman from Texas put it *12 plainly: “If we could not control the Mexicans and they would take this country it would be better to keep them out, but we can and do control them.” Migra! 29 (quoting Paul Schuster Taylor, An American-Mexican Frontier, Nueces County, Texas 286 (1971)). When questioned about the possibility that Mexicans might permanently settle in the United States, Frisselle offered that “the Mexican pretty well solves that problem himself. He always goes back [to Mexico].” Frisselle Testimony 14. But to the extent that more assurances were needed, he promised to keep the Mexican population in check: “We, in California, think we can handle that social problem.” Migra! 29 (quoting Frisselle Testimony at 6). To that end, Frisselle highlighted an ongoing effort to set up labor organizations across the state that could shuffle immigrant workers from region to region throughout the year in accordance with different crops' harvesting periods. Frisselle Testimony 13-15. The goal, as he put it, was to get migrants “out of the congested areas” where they were “congregating” (like Los Angeles) and “keep them moving.” Id. at 14-15.

Yet as time passed, the facts on the ground changed. By 1929, 10% of the Mexican population already lived in the United States, Los Angeles was home to the second-largest Mexican community in the world, and “small Mexican communities were developing as far north as Detroit.” City of Inmates 136-137. The Nativists may have once been content with the agricultural industry's promises that it could, as Frisselle put it, “handle” the Mexican “problem,” but by 1929 agribusiness's assurances of Mexican impermanence looked increasingly illusory.

*13 D. The Criminal Entry And Reentry Provisions Of The Undesirable Aliens Act Of 1929 Were Crafted As A Solution To The “Mexican Problem”

Ultimately, the two sides resolved their differences over how to deal with the “Mexican problem” by creating the unauthorized entry and reentry statutes. As the 1920s wore on, Nativists' patience was wearing thin. But the economy of the Southwestern United States remained critically dependent on Mexican immigrant labor. Crafting a legislative policy that imposed draconian limits on the number of Mexicans who could cross the border was politically infeasible, even if both sides of the debate shared a white supremacist disdain for the Mexican immigrant community. The ground was fertile for a compromise, and Senator Coleman Livingston Blease-with the help of Secretary of Labor James Davis-proposed a way to mollify both the Nativists and the agribusiness lobby. His idea would eventually become the Undesirable Aliens Act of 1929, including its provisions criminalizing unauthorized entry and reentry after deportation.

According to one biographer, Senator Blease exhibited a “Negro-phobia that knew no bounds.” City of Inmates 137 (quoting Kenneth Wayne Mixon, The Senatorial Career of Coleman Blease 5 (1967) (The Senatorial Career) (M.A. thesis, University of South Carolina)). Blease began his career in government in the South Carolina state assembly, where “his first legislative proposal was a bill to racially segregate all railroad cars in South Carolina.” Ibid. He later became the state's governor before being elected to the U.S. Senate in 1925. Ibid.

Senator Blease telegraphed his views on race openly during his single term in Congress. For example, he spoke out against the establishment of a world court because he could not stand the thought of a “court where we [Anglo-Americans] are to sit side by side with a full *14 blooded ‘[n*****].’ ” City of Inmates 137 (quoting The Senatorial Career 30).

In another incident, after First Lady Lou Hoover invited the African American wife of a congressman to tea at the White House, Senator Blease attempted to introduce a formal resolution demanding that the president and his wife “remember that the house in which they are temporarily residing is the ‘White House.’ ” $%^3 Within the resolution was the text of a poem titled “[N******] in the White House,”which Senator Blease asked to be read into the congressional record. $%^4 Upon objection from a fellow legislator, Senator Blease agreed to withdraw it from the record. 71 Cong. Rec. 2946-2947 (1929). But Senator Blease wanted to make his reason very clear: “I have accomplished what I wanted by having it read here[.] * * * [I]n withdrawing it from the record I am doing it because it gives offence to the Senator from Connecticut and not because it may give offence to the [n******].” $%^5

As noted above, Senator Blease did not act alone in crafting the 1929 Act. He was assisted by Secretary of Labor James Davis, who was a strong advocate of Dr. *15 Harry H. Laughlin's eugenics theories. $%^6 See Hans P. Vought, The Bully Pulpit 173 (2004). Secretary Davis had previously warned of the “rat-men” coming to the United States via the southern border who would jeopardize the American gene pool. James J. Davis, The Iron Puddler: My Life in the Rolling Mills and What Came of It 61 (1922). Like others, he criticized the 1924 Act for closing “the front door to immigration,” while leaving the “back door wide open.” James J. Davis, Selective Immigration 207 (1925).

After the 1924 Act was passed, Davis sponsored a study by Princeton economics professor Robert Foerster on the subject of the “racial problems” of Latin American immigration. Robert F. Foerster, Report Submitted to the U.S. Dep't of Labor, The Racial Problems Involved in Immigration from Latin America and the West Indies to the United States (1925). The report was subsequently incorporated into the permanent records of the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization of the House of Representatives as it discussed the potential revision of the 1924 Act. Immigration from LatinAmerica, the West Indies, and Canada: Hearings Before the House Comm. on Immigration and Naturalization, 68th Cong., 2d Sess. 303-338 (1925). In his report, Professor Foerster provided a racial analysis of Mexico and every country located south of the U.S. border, finding that most of their inhabitants were Indian, Black, or mixed race, all of which he described as “dubious race factor[s].” Id. at 334-335. *16 He strongly advised that further immigration from south of the border be curtailed because “when an immigrant is accepted by the country, a race element or unit is added into the race stock of the country.” Ibid.

Senator Blease and Secretary Davis also found allies in the House of Representatives. First there was Representative John C. Box, discussed supra, who considered the goal of immigration law to be “the protection of American racial stock from further degradation or change through mongrelization.” 69 Cong. Rec. 2817 (1928). The second was Representative Albert Johnson, Chair of the House Immigration and Naturalization Committee, who also headed the Eugenics Research Association. Daniel Okrent, The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics, and the Law that Kept Two Generations of Jew, Italians, and Other European Immigrants out of America 271, 326 (2019). Turning to legislation that would exclude the “Mexican race” following the 1924 Act, Representative Johnson explained that while prior reform was economically motivated, now “the fundamental reason for it is biological.” Id. at 3 (quoting Albert Johnson, Immigration, a Legislative Viewpoint, Nation's Bus., July 1923, at 26, 26).

In 1929, Senator Blease and Secretary Davis saw an opportunity to broker a legislative compromise that would address the political debate over Mexican immigration. Their idea would not impose any cap on authorized immigration-as had been fruitlessly attempted-but instead would regulate so-called “unauthorized” migration. They thus proposed legislation that would criminalize unlawful entry into the United States for the first time in the nation's history. City of Inmates 137. “[U]nlawfully entering the country” would become a misdemeanor punishable by a $1,000 fine, up to one year in prison, or both. Id. at 138 (quoting Act of March 4,1929, Pub. L. No. 70-1018, ch. *17 690, § 2, 45 Stat. 1551). “Unlawfully returning to the United States after deportation” was classified as a felony, punishable by a $1,000 fine, up to two years in prison, or both. Ibid. (emphasis added). Agribusiness was onboard; they liked the idea of taking advantage of inexpensive labor when they needed it, and making those people disappear at the end of the harvest. See id. at 138 (citing Frisselle Testimony at 8 (“We, in California, would greatly prefer some set up in which our peak labor demands might be met and upon the completion of our harvest these laborers returned to their country.”)).

Notably, the statute did not punish overstaying a visa, only unauthorized entry and reentry after deportation. Thus, it authorized punishment for those who crossed by land-who were overwhelmingly Mexicans-rather than those who overstayed their authorized period of admission-who were overwhelmingly Europeans.