Become a Patreon!

Abstract

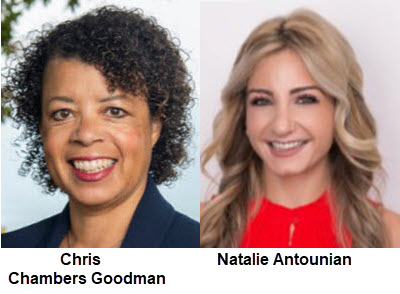

Excerpted From: Chris Chambers Goodman and Natalie Antounian, Dismantling the Master's House: Establishing a New Compelling Interest in Remedying Systemic Discrimination, 73 Hastings Law Journal 437 (February 2022) (215 Footnotes) (Full Document)

Then: Proposition 187 denies services to undocumented immigrants in California. Aspiring gubernatorial candidate Pete Wilson champions Proposition 209, which eliminated affirmative action in California public education, employment, and contracting. Similar initiatives carried over to other states.

Then: Proposition 187 denies services to undocumented immigrants in California. Aspiring gubernatorial candidate Pete Wilson champions Proposition 209, which eliminated affirmative action in California public education, employment, and contracting. Similar initiatives carried over to other states.

Now: Black Lives Matter. DACA continues. Qualified immunity for misuses of deadly force is up for review. In higher education, the use of affirmative action has been repeatedly upheld, but the Supreme Court is considering whether to grant a hearing in the latest case involving Harvard College. In California, Proposition 16, which would have overturned Proposition 209, was voted down on the November 2020 ballot, thus continuing the state's prohibition on considering race, ethnicity, color, national origin, or gender in public contracting, employment, and education. Polls show that a majority of the public support affirmative action generally, but oppose the specific use of race and ethnicity in making hiring and admissions decisions. Thus, voter initiatives are not the best way to try to entrench and preserve affirmative action in higher education.

Recent litigation brought cause for concern, but Harvard successfully defended the anti-affirmative action lawsuit at the trial and appellate stages. The University of North Carolina (UNC) had its trial in November 2020, where the Court found that the University did not discriminate against white and Asian American applicants in admission. Thus, litigation has been successful, to a point, in preserving affirmative action. But the composition of the current U.S. Supreme Court suggests that the majority will be receptive to plaintiffs challenging affirmative action programs. Support of the diversity and inclusion rationales may be waning, and the 2028 “sunset” clause language in Justice O'Connor's Grutter opinion provides a strong justification for the Court to reconsider diversity as a compelling government interest in higher education before the end of this decade. Equity abhors a vacuum, and so this Article promotes a return to remedial justifications for affirmative action programs and policies.

Since Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education and City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., the U.S. Supreme Court has held that remedying “societal discrimination” is not a compelling interest to justify race-conscious programs, but remedying present discrimination is. This Article posits that “institutional discrimination” is past discrimination multiplied and perpetuated. It will analyze how dismantling institutional discrimination meets the compelling government interest in remedying past discrimination. Just as separate was inherently unequal, restricting government actors from taking race-conscious steps to reduce and eventually eliminate institutional discrimination means inequities will remain.

When segregation is de facto, which means that it is not based on laws but rather based on individual choices, the current Supreme Court doctrine holds that it violates the Constitution to take racially explicit steps to reverse it. Because the Court majorities have viewed racial discrimination as occurring when a racist individual externalizes, or intentionally acts upon, feelings of bias and prejudice, it is also fair to say that racial discrimination occurs when institutional processes function to unfairly disadvantage a racial group. Thus, de facto discrimination should be remediable; it should be considered a compelling interest sufficient to justify a race-conscious remedy under the strict scrutiny test. In the education context, for instance, it illustrates the unfair and discriminatory treatment many minority students experience under a school district's “race-neutral policies.”

Part I of this Article begins with an overview of the strict scrutiny standard, providing background on what are and are not compelling government interests, and what meets the narrowly tailored element. After exploring the Court's dismantling of the societal discrimination justification for affirmative action programs, Part II makes the case that remedying institutional discrimination is equivalent to remedying past and present discrimination and therefore should be a compelling government interest. The artificial distinction between de jure and de facto discrimination ignores the law's complicity in constructing institutional and systemic discrimination. As Adarand deconstructed the distinction between invidious and benign preferences, years of social science research and data have shown that the present effects of past discrimination have maintained racial disparities along nearly every facet of American life, including employment, wealth, education, home ownership, health care, and incarceration. Part II also explains how a different and more inclusive outcome regarding the Court's interpretation of de facto segregation would be an appropriate change to reduce the impact of current systemic discrimination in our nation's public education system.

Part III analyzes the evidence showing how existing affirmative action policies help combat the effects of institutional discrimination through the lens of the current litigation at the University of North Carolina, the recent Harvard trial, and the outcomes at the University of California schools (the “UCs”) after the elimination of affirmative action in 1996, which undermined that system's ability to realize the compelling government interest in obtaining the educational benefits that flow from diversity. The potential sunset of the diversity justification in higher education means that other strategies need to be developed now to fill the void that could occur before 2028. Part IV concludes the Article with a brief discussion of why U.S. Supreme Court litigation is not likely to preserve affirmative action, and suggests that a better route is in drafting model legislation, building off the requirements in Title VI, to mandate affirmative action in public education as a remedy for institutional and systemic discrimination.

[. . .]

In conclusion, this Article demonstrates that systemic/institutional racism is past and present discrimination compounded and multiplied. Therefore, remedying institutional discrimination should be considered a compelling government interest to justify race-conscious remedies, and the fake dichotomy of de jure and de facto segregation and discrimination should be dismantled.

The current U.S. Supreme Court is not likely to consider this claim and thus congressional legislation is the preferred approach. Admittedly, it is a tough sell in the House and Senate, and there are about nine months left to try before the midterm elections. Some may suggest using an Executive Order, but the “policy whiplash” that results from a change in administrations would put a substantial burden on colleges and universities, not to mention students and applicants, especially given the greater financial and other strains due to the COVID-19 crisis.

Given the narrow majorities in Congress, and the fact that not all Democratic congresspersons are supportive of race-based affirmative action, a compromise proposal that combines class and race-based affirmative action might be necessary to obtain support from a majority of the House and Senate. Let us begin. Now is the time to start the negotiations, while the sun remains high in the sky, before sunset arrives.

Straus Research Professor and Professor of Law, Pepperdine Caruso School of Law; J.D., Stanford Law School; A.B. cum laude, Harvard College.

Attorney, J.D. Pepperdine Caruso School of Law (2021), M.D.R Pepperdine Caruso School of Law Straus Institute for Dispute Resolution (2021), B.A. University of Southern California (2018).

Become a Patreon!