Abstract

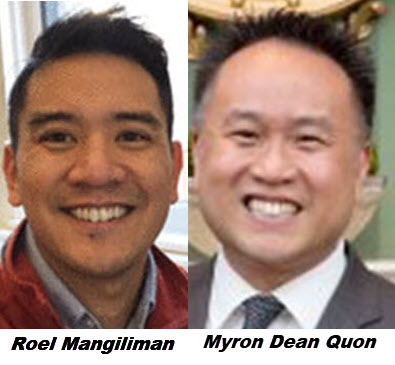

Excerpted from: Roel Mangiliman and Myron Dean Quon, In the Margins: How Mainstream Legal Advocacy Strategies Fail to Fully Assist Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander LGBT Youth, 19 Asian American Law Journal 5 (2012)(160 Footnotes) (Full Document)

In many ways, Charlene Nguon was the ideal student. She received straight-A's, the praise of her teachers, and was an active participant in extracurricular activities. At the start of her junior year of high school, Charlene had two main goals: first, to maintain her high grades and second, to join the National Honor Society. Simply put, Charlene planned for college and was well on her way.

In many ways, Charlene Nguon was the ideal student. She received straight-A's, the praise of her teachers, and was an active participant in extracurricular activities. At the start of her junior year of high school, Charlene had two main goals: first, to maintain her high grades and second, to join the National Honor Society. Simply put, Charlene planned for college and was well on her way.

However, just a few months removed, her plans fell apart at the seams. Although Charlene was indeed invited to join NHS, her invitation was subsequently revoked during that same academic year. During this time, Charlene found herself at the center of a school controversy, which eventually led to her school suspension and forced transfer to another high school. This drastic change of fortunes completely altered Charlene's outlook on life; the once-overachieving high school student became depressed and even contemplated suicide.

This downward spiral of events began in 2005 when Santiago High School suspended sixteen-year-old Charlene for the on-campus display of affection towards her girlfriend, Trang Nguyen. According to Charlene, she was unfairly targeted for punishment based on her sexual orientation. Although she was formally suspended for showing affection towards her girlfriend, her gender-conforming classmates were frequently allowed to hold hands and kiss without any type of formal or informal reprimand. Charlene described such acts as commonplace behavior at her high school. Her peers further suggested that they did not have any problem with her and Trang's affection. Nevertheless, school administrators repeatedly singled them out for punishment.

Santiago High School's principal, John Wolf, was authorized by school policy to disclose the reasons behind Charlene's suspension to her parents. In a meeting with Charlene's mother, Wolf shared that Charlene was suspended for “kissing another girl,” thus revealing Charlene's sexual orientation without her notice or consent. This obtrusive revelation caused Charlene great anguish and strained her relationship with her family. Immediately thereafter, she became depressed and suicidal, which contributed to her subsequent poor academic performance. Because of her drop in grades, Charlene's offer for admission to the University of California, Santa Barbara was withdrawn.

Represented by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Charlene later sued the school district based on claims of sexual orientation discrimination, and for violating her right to privacy regarding her sexual orientation. The pleas were not well taken, as the court found for the school on all claims. With respect to the allegations of prohibited discrimination, the trial court ruled that there was inconclusive evidence to establish that the administrators singled out Charlene and Trang among non-lesbian couples. As to the privacy claim, the court held that the school justifiably disclosed her orientation, due to the overriding state interest of providing Charlene's parents with a “meaningful opportunity to discuss and challenge the allegations of misconduct.” Ultimately, Charlene was left without any legal recourse or financial compensation. What remained, however, were the derailment of Charlene's college-track plans and the fresh cuts on her arms-- self-inflicted wounds from her battle with depression and suicide.

Charlene's tragic experience provides a compelling case study for broader sociological and legal comment. Several studies have framed depression and suicide as endemic to Charlene's community. As a self-identified lesbian, Cambodian-American, and teenager, Charlene is one of countless Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (APA LGBT) youth who have struggled or currently struggle with mental health and well-being issues. According to a study by the National Center for Health Statistics, Asian American girls ages fifteen to twenty-four commit suicide at a rate higher than any other racial group. Another study reports that lesbian, gay, or bisexual youth are two to three times more likely to commit suicide than their non-gay peers. Taken together, these reports suggest an alarming pattern. While these studies do not directly collect data or provide analysis concerning APA LGBT youth in particular (devoid of APA male youth studies), their limited findings concerning ethnicity, sexual orientation, and their disparate impact on certain individuals convey amplified suicidal-risk factors for those living at this intersection.

Despite the potential vulnerabilities of APA LGBT youth, the failings of the judicial system to assist an APA LGBT youth like Charlene is not an isolated incident. While Charlene's case was tried in court, many APA LGBT youth are not able to get that far with the judicial system. Through examining empirical data, as well as legal scholarship, it appears that neither substantive law nor mainstream legal strategies fully respond to the legal needs of many APA LGBT youth. This inadequacy is clearly seen through the lens of Charlene's unsuccessful lawsuit. More interestingly, this shortfall is further evidenced by the absolute lack of legal scholarship devoted to analyzing the needs of the APA LGBT community. A critical analysis will reveal that APA LGBT youth have a profoundly tenuous relationship with the law.

This Article will discuss and critique this tenuous relationship between the law and APA LGBT youth. APA LGBT youth stand as a compelling example of a vulnerable community--one that faces exposure to racism, homophobia, and mental health battles--that, for unknown reasons, are markedly disassociated from using the courts. This Article traces this estrangement to a slew of practical barriers that make legal relief improbable for an APA LGBT. Such obstacles range from the tremendous difficulty in contacting a lawyer, to an inadequate body of substantive legal protection. As a result, unless steps are taken to address this problem, APA LGBT youth community will remain largely excluded from the possibility of legal justice.

Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth, herein shortened to APA LGBT youth, are a group virtually absent in jurisprudential archives and sociological research.

Therefore, to begin discussing this community, Part II of this Article will synthesize data to provide a portrait of the group, noting baseline demographics and issues surrounding ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation.

Part III discusses the legal gains made by the APA and LGBT communities, despite the hardships they face, in areas such as hate crimes, language assistance, and quests for LGBT friendly spaces in public schools.

Part IV will carefully analyze and critique these very gains by drawing attention to the overlooked and precarious ways in which APA LGBT youth are practically deterred from contacting a lawyer, as well as attaining any real chance of substantive legal relief true to their intersectional experience. Having articulated the need for lawyers to take a more imaginative approach,

Part V looks at “community lawyering,” alternative to traditional lawyering, that provides a way for lawyers to improve services to APA LGBT youth. To illustrate the advantages of this alternate approach,

Part VI demonstrates how community lawyering could have potentially improved Charlene's legal advocacy and, more importantly, her welfare overall.

[. . .]

Although this article is focused on the crucial and specialized circumstances unique to APA LGBT youth, all legal advocates are urged to begin thinking about the holistic needs of multiple-identity communities. In a nation alive with increasing pluralism, legal advocates must respond to the needs of diverse communities. They must “relearn” that legal work is more interdisciplinary than law schools suggest, that “personal failure to use the law” might have systematic causes, and that the justice system might not comprehend the plight of multiple-identity minorities. In using APA LGBT youth as an example, a broader vision of advocacy that encompasses multiple-identity groups--such as the re-imagined, rebellious notions of lawyering--are better drawn from the margins, and more appropriately served by the legal community.

Judicial Administration Fellow, Access Center, San Francisco Superior Court. J.D. 2012, University of California at Davis; B.A. 2009, University of California at San Diego.

Executive Director, NAPAFASA

Please visit my Patreon Page