Abstract

Excerpted From: Jessica Dixon Weaver, The Ties That Bind: What Pauli Murray Teaches Us about Race, Family, Slavery, and Inequality, 55 Family Law Quarterly 293 (2021-2022) (157 Footnotes) (Full Document)

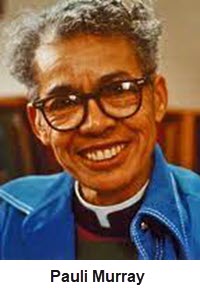

Pauli Murray is an unsung American hero. She was a civil rights activist, a feminist, a lawyer, a book author, a poet, a professor, and a priest. She was a trailblazer--the first Black person to earn a doctorate in law from Yale University, one of the co-founders of the National Organization of Women (N.O.W.), and the first African American female ordained Episcopal priest. Pauli Murray was down-right revolutionary--she was sitting in the front of the bus before Rosa Parks and sitting in at the lunch counter more than 15 years before the Greensboro Four. She wrote the “Bible” of the Civil Rights Movement, a 1950s book entitled States' Laws on Race and Color. Her law school thesis entitled “Should the Civil Rights Cases and Plessy Be Overruled?” contained the foundation of the arguments used by Thurgood Marshall in Brown v. Board of Education. She coined the term “Jane Crow” while she was a student at Howard University School of Law to describe the similarities between the legal discrimination of Blacks and women, and later co-wrote a law review article published in the George Washington Law Review that was the first comprehensive treatment of sex discrimination in an American law review. Ruth Bader Ginsburg added Pauli Murray's name to the Appellant's Brief filed in the Reed v. Reed case because she used Pauli's argument from the law review article. Ultimately, it was Pauli's legal analysis used in the first Supreme Court case that held that the Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause supported the prohibition of differential treatment based on sex. After Thurgood Marshall was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967, Pauli wrote to President Richard M. Nixon in 1971 to offer her availability and readiness “to serve on the high court should he wish to nominate a woman.” In addition to all of the legal monuments she helped erect, she was a person who identified as a male trapped within a female body, and lived her life as a lesbian. The modern-day understanding of equality--and the legal arguments used to obtain it for Blacks, women, and the LGBTQ community--were the brainchild of Pauli Murray.

Pauli Murray is an unsung American hero. She was a civil rights activist, a feminist, a lawyer, a book author, a poet, a professor, and a priest. She was a trailblazer--the first Black person to earn a doctorate in law from Yale University, one of the co-founders of the National Organization of Women (N.O.W.), and the first African American female ordained Episcopal priest. Pauli Murray was down-right revolutionary--she was sitting in the front of the bus before Rosa Parks and sitting in at the lunch counter more than 15 years before the Greensboro Four. She wrote the “Bible” of the Civil Rights Movement, a 1950s book entitled States' Laws on Race and Color. Her law school thesis entitled “Should the Civil Rights Cases and Plessy Be Overruled?” contained the foundation of the arguments used by Thurgood Marshall in Brown v. Board of Education. She coined the term “Jane Crow” while she was a student at Howard University School of Law to describe the similarities between the legal discrimination of Blacks and women, and later co-wrote a law review article published in the George Washington Law Review that was the first comprehensive treatment of sex discrimination in an American law review. Ruth Bader Ginsburg added Pauli Murray's name to the Appellant's Brief filed in the Reed v. Reed case because she used Pauli's argument from the law review article. Ultimately, it was Pauli's legal analysis used in the first Supreme Court case that held that the Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause supported the prohibition of differential treatment based on sex. After Thurgood Marshall was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967, Pauli wrote to President Richard M. Nixon in 1971 to offer her availability and readiness “to serve on the high court should he wish to nominate a woman.” In addition to all of the legal monuments she helped erect, she was a person who identified as a male trapped within a female body, and lived her life as a lesbian. The modern-day understanding of equality--and the legal arguments used to obtain it for Blacks, women, and the LGBTQ community--were the brainchild of Pauli Murray.

Dr. Murray wrote two books: a memoir about her family and another autobiography about her life. Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family (Proud Shoes) is a saga about the Fitzgerald family from the early 1800s to the beginning of the 20th century. Initially published in 1956, it is a Black woman's history of her family's journey through slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction, written over 20 years before the famous book Roots by Alex Haley. In fact, Dr. Murray states that Proud Shoes portrays the entanglement of the races, not as a unique story, but as an acceptance of the reality of the multiracial origins of both Blacks and whites.

Dr. Murray's family history is emblematic of the struggle for racial justice and equality in America. The pain and tenacity of her ancestors shaped her destiny and spurred her activism. Her family experiences illustrate the many ways that the foothold of structural racism began with placing insurmountable legal barriers between Black men, women, and children as a family unit. The law has played a calculated role in separating the races as families from an ideological perspective. In other words, the construct of race and the inferiority and superiority complexes that accompany it allowed for the legal exclusion of family members within family units. This legal exclusion rendered the identity of formerly enslaved persons invisible in some families, and it often disrupted the structure of what was deemed as the normative family. Dr. Murray's family story is about the ties that bind us as families in America.

[. . .]

Understanding the history of family law is accepting the construction of race and the power dynamic of families within race relations. Slavery was contingent on laws regulating Blacks as inferior. The only way that U.S. law could configure a system to support slavery was to flip family law on its head. Pauli wrote about it in her autobiography, stating, “[f]ew white people in the South wanted to acknowledge blood ties between the races created by the slave-owning class during slavery.” If we were to truly accept how families came to be physically formed in America--and the government's role in the denial of Black family life, growth, and death--we would have a better understanding of the true arc of justice.

Slavery laws and the use of race as a social construct have been integral to the development of family laws in our country. There were two separate legal systems that governed white families and Black families--common law for whites and slavery law for Blacks. Because slaves were treated as extralegal--outside of the law--there was a divide between how Black families were treated as compared to white families. This divide continued beyond emancipation and is still present in the regulation of families today.

Pauli's family shows us that race and family are fluid and complex. Pauli Murray teaches us that family ties and the function of families often define and transcend racial differences among people. While family ancestry can be painful and shameful, it is a powerful motivator to fight inequality. Pauli saw her grandfather Robert George Fitzgerald as the person in her family who established their official place in American history, and her ancestors' example of courage fueled her own political activism.

Slavery was not only a physical condition, but it was also a mental one as well. Because it was an institution built upon a belief system of inferiority of the Black race grounded in false morality and science, it has been a difficult condition to overcome for both Blacks and whites. Well after enslaved persons were emancipated in 1865, the laws of slavery and the condition they supported still exist as the backdrop to race relations in the United States.

Pauli Murray spent her entire life teaching and educating others about how the law and the spirit could be used to provide equality and dignity for each person. Though she struggled with how people viewed her mixed ancestry and sexual identity, she believed in treating people as human beings and members of the same human family. The stories of the Smiths and the Fitzgeralds played a role in generating a revolt in her, and she shared the proud heritage of both Robert Fitzgerald and Cornelia Smith. Perhaps embracing the different sides of American family history--free and enslaved, white and Black--will began a long-awaited healing that is Pauli Murray's legacy.

Professor Jessica Dixon Weaver is Professor of Law and a Robert G. Storey Distinguished Faculty Research Fellow and Gerald J. Ford Research Fellow at SMU Dedman School of Law.