Become a Patreon!

Abstract

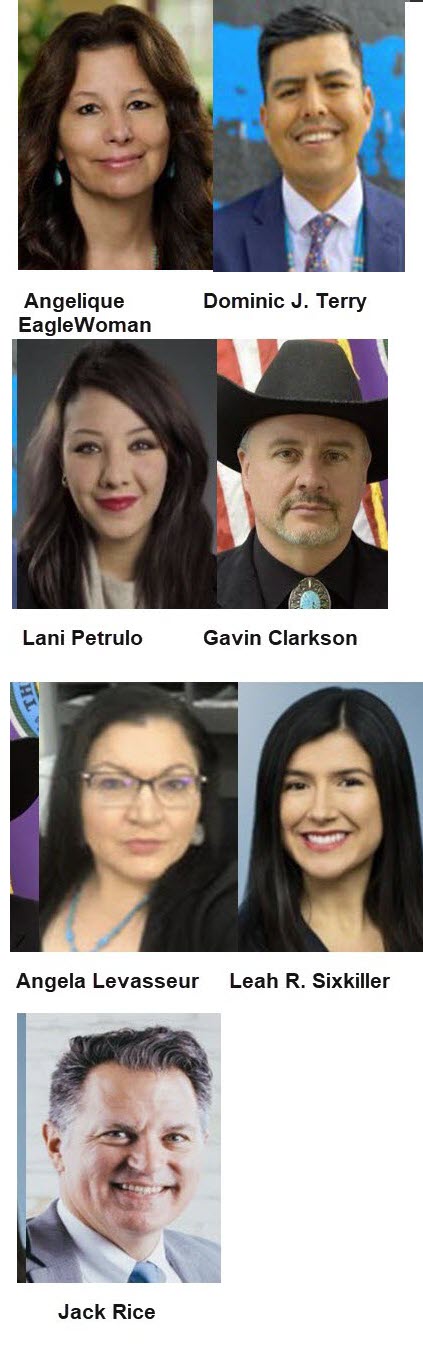

Excerpted From: Angelique EagleWoman (Wambdi A. Was'teWinyan), Dominic J. Terry, Lani Petrulo, Dr. Gavin Clarkson, Angela Levasseur, Leah R. Sixkiller and Jack Rice, Storytelling and Truth-telling: Personal Reflections on the Native American Experience in Law Schools, 48 Mitchell Hamline Law Review 704 (May, 2022) (95 Footnotes) (Full Document)

In January of 2021, the American Association of Law Schools (“AALS”) theme was Freedom, Equality and the Common Good. The Indian Nations and Indigenous Peoples Section of the AALS embraced the theme and announced a call for personal reflections incorporating the experiences of Native Americans in law schools. The theme of striving for academic freedom and equality allows for an in-depth questioning of whether Native Americans have been adequately and appropriately represented in legal curricula in the nation's approximately two hundred law schools. The aspirational goal of realizing the common good must be inclusive of Native American voices as students, faculty, staff, and graduates and in curricula choices in law schools across the country.

In January of 2021, the American Association of Law Schools (“AALS”) theme was Freedom, Equality and the Common Good. The Indian Nations and Indigenous Peoples Section of the AALS embraced the theme and announced a call for personal reflections incorporating the experiences of Native Americans in law schools. The theme of striving for academic freedom and equality allows for an in-depth questioning of whether Native Americans have been adequately and appropriately represented in legal curricula in the nation's approximately two hundred law schools. The aspirational goal of realizing the common good must be inclusive of Native American voices as students, faculty, staff, and graduates and in curricula choices in law schools across the country.

There has been sparse legal scholarship on the experience of Native American applicants, law students, faculty, and staff in law schools. The Indigenous perspective essays in this compilation are an opportunity to hear the voices of Indigenous peoples on their lived experiences in seeking law degrees and careers in law-related fields. Words such as resiliency, endurance, and perseverance often come to mind when Native Americans discuss their personal experiences in the legal academy. The following collection of essays are a contribution to the legal academy in the Indigenous tradition of storytelling shared as firsthand accounts through the seven authors' perspectives. Within the personal reflections, the tenacity of Native people to succeed and overcome barriers is a common theme. Many of the contributors speak to the value of mentoring or becoming a Native lawyer to serve as a mentor. The compilation provides insight into the experience the authors share of a deep commitment to their Indigenous communities and to trailblazing for the next generation of Native lawyers.

The first essay in the compilation is Becoming a Native Lawyer by Dominic Terry (Navajo Nation/Diné). His contribution is motivated by his desire to “share my story in hopes that it inspires Native children to believe in themselves.” He details the struggles of surviving a broken home, poverty, and teachers with low expectations, and worse, derogatory comments from his childhood and teenage years. Drawing on his grandmother's love and determination, he persevered when an injury sidelined his dreams of a football career and re-dedicated himself to pursuing his undergraduate degree after finding himself off-track. A poster in the back of a classroom planted the seed that he could attain a law degree.

With few examples of Navajo college or law graduates, Dominic decided to serve as an inspiration and role model by becoming a Navajo lawyer. Taking the Law School Admissions Test (“LSAT”) twice to gain admission to law school, he explains, “[l]aw school was exactly what I expected- tough.” Major life changes occurred for him as a law student as he moved across the country to attend law school, fathered a newborn, and adopted his nephew. His resiliency was again tested when he failed the Minnesota bar examination and eventually triumphed on the fourth attempt. He remembered his grandmother's words to never give up. The personal essay concludes with Dominic contributing as a lawyer in the Child Protection Division as an Assistant Hennepin County Attorney in the Minnesota Twin Cities area. Through his many difficult experiences, he finds the sacrifices were worth it as he can now state that “[m]y position allows me to be a voice for the Native community.”

The second essay is titled, Barred: A Personal Reflection on the Native American Experience in Legal Academia, by Lani Petrulo (Native Hawaiian). In her essay, she writes, “[a]lthough Native Hawaiians are treated differently under most federal laws and policies than members of federally recognized tribes, they are still connected to their Indigenous brothers and sisters through shared cultural values that live on today.” In detailing her ancestral history as a Native Hawaiian, Lani explains that the lack of inclusion in both mainstream legal curricula and in curricula focused on American Indians and Alaska Natives can be painful and traumatizing. She shares that “learning and practicing in the field of Native American law can bring up many painful and unresolved issues related to generational trauma, but also involving confusion of cultural identity.” She names the experience of “Native imposter syndrome” as connected to the invisibility for her as a Native Hawaiian woman in the legal field.

As in the prior essay, the theme of making a difference for future generations is present in Lani's essay. Due to the uncertainty around Native Hawaiian political status, she cites to the multiple barriers she faced when applying for scholarships, the limited spots for Native Hawaiians in the one law school in Hawaii, financial stressors, and the emotional toll from the impending occupation of “Maunakea, one of the most sacred sites in Hawaiian culture, believed to be an ancestor of the people.” Following her Juris Doctor (“J.D.”) and Master of Laws (“LL.M.”) degrees, she currently works as a judicial law clerk and has the goal of joining the legal academy to become a law professor and “ultimately be the Native Hawaiian representation that I never had.”

Next is my personal essay in this compilation titled, Making a Community and Taking a Stand: Reflections on Law School from a Dakota Woman. In the essay, I speak of racial injustice and broken U.S. government treaty promises as motivating my dream of being a Native lawyer from a young age. My lived experience included a lack of stability in my early home life requiring ongoing focus to attain high grades which led to acceptance at Stanford University. After graduating with a degree in political science, I questioned my path to a law degree and ultimately attended the law school closest to my reservation to avoid homesickness. During law school, I participated in “demonstrations and small teach-ins on why the University mascot was dehumanizing towards my people and our sister Tribes.” My experience in law school was often a lonely one as the only Native law student in most law classrooms and in my graduating class.

After becoming a lawyer and a single mother, I returned to law school to earn my LL.M. degree in American Indian and Indigenous Law. The faculty in the LL.M. program encouraged my development in the law and allowed me to confidently apply to be a law professor. Currently, I am a law professor and director of the Native American Law and Sovereignty (“NALS”) Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law (“MHSL”) in Saint Paul, Minnesota. In the legal academy, there are very few Native Americans and “fewer Native women, who have attained the rank of tenured law professor in the two hundred plus law schools in the United States.” While my path was a winding trail, the strength of elders and ancestors helped me along to encourage the next generation of Native lawyers. “Through my example and advocacy, I hope to ensure that the doors of law schools stay open to Native women and men students and that there are resources of community, financial assistance, and cultural understanding for these same students to succeed.”

The fourth contribution highlights the importance of mentoring by Dr. Gavin Clarkson (Choctaw Nation) and is titled, My Indian Law Journey. With both parents escaping poverty and instilling the value of education, Gavin pursued a career as a professor in the field of computer science as a self-labeled “nerdy Native.” He attained degrees from Harvard University and after a decade of teaching was encouraged by mentor and visiting law professor Robert A. Williams to consider becoming a Native law professor. “If I wanted to solve any of the problems I had witnessed in the Choctaw Nation and elsewhere, becoming an Indian law professor would provide such an opportunity.” With the goal of infusing tribal economic development into the legal academy curriculum, Gavin pursued his law degree to complement his doctorate in business.

Professor Williams steadfastly served as a mentor while Gavin advocated a variety of perspectives on initiatives that combined tribal economics and tribal sovereignty. He noted that, at times, he faced opposition within the field of law and took his mentor's advice to keep focused on his research. This led to the publication of law review articles on tribal finance, testimony on tribal access to capital markets, and eventually a position with the Trump Administration to serve in the U.S. Department of the Interior as the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Policy and Economic Development. “Although Professor Williams and I disagree on many political issues off-reservation, he was able to look past those differences and think outside the box about how I might contribute and make a difference in other people's lives throughout Indian Country,” he explains.

Next, third year law student, Angela Levasseur (Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation) contributed her personal essay titled, Native American Legal Experience: A Cree & Dakota Grandmother's Perspective. To provide insight into her experiences as a law student, Angela determined five areas of focus as “trauma and intergenerational trauma; the importance of mentors and role models, poverty and the consequential financial struggles; systemic racism and discrimination; and finally; culture shock.” From the experiences of her ancestors, her tribal history and her own personal lived experiences, Angela declares “these experiences have made me extremely resilient.” She also credits mentors and role models with demonstrating that she too could complete her legal education as “others have broken the trail for you and are actively cheering you on.”

She relates how a case taught in her first-year criminal law course about a Native American family did not include instruction on the context, the cultural forces at work or the tragedy of the events depicted. Angela felt obligated to provide the class with a history lesson on the removal of Native children and the context for the course material. This and other similar experiences around the lack of context for Native American issues are described as “exhausting” as she pursues a law degree. She also experienced “culture shock” from the lack of Native American imagery and space within the law school building. These experiences have inspired her to set the goal to “practice law for several years in service to my tribe and then become a Native law professor.”

The sixth reflection is by attorney and tribal judge Leah Sixkiller (Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians) sharing experiences in her essay, Reflection Paper. She noted that “my law school experience is exceptional and perhaps unbelievable to some.” After graduating from Harvard University, Leah attended law school in Arizona within a well-developed program where she attained the Certificate of Indigenous Peoples Law and Policy. She felt welcomed, celebrated and in a law school where Indian law was recognized as important for all law students. “For the first time in my entire life, I was not part of the unheard ultra-minority in an institutional setting, but rather of the outstanding and celebrated minority,” she explains.

Leah provided her lived experience as an example of best practices to support and uplift Native American law students. “To all of a sudden be a part of a sizable and vibrant American Indian educational community at [the University of Arizona College of Law] both floored me and added to my self-confidence and sense of self-worth, thus propelling me to work toward excellence and seek the most competitive opportunities.” As she reflects on her life in the law, she has found her motivation was to make her family proud. Leah shared, “I am standing on their and my ancestors' shoulders, and I have a duty to do and be the best.”

The seventh and final reflection is Why I Fight for Equity in the Criminal Justice System by Jack Rice (San Luis Rey Band of Luiseno Indians), criminal defense attorney and international trial advocacy trainer. He reflects on the impoverished conditions of his early years and the encouragement of his single mother telling Jack and his brother that they could achieve their dreams. “Coming from where she came from and from what she endured, I'm still blown away by her tenacity, her wisdom,” he explained. Dealing with racism and a history of ancestral genocide, Jack viewed his law school experience as failing to incorporate other perspectives on the law. The adversarial model of law “frequently ignored other forms and approaches including Native American ones that could be more effective.” He relates how he successfully employed a Native American restorative approach to a case that gained national attention due to the pulling down of the Christopher Columbus statue in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Jack has practiced in the criminal defense field for decades and provides trial advocacy training in countries around the world. As a new lawyer, he witnessed a judge take the time to provide a comfortable space and respectfully listen to his client who was a “poor, drug addicted, sexually abused” Native American woman. This judge demonstrated an open mind, and that the court had an obligation to justice as much as the defendant. This courtroom experience was pivotal in providing him hope that the criminal justice system could be positively influenced by the morals of judges, lawyers, and jurors towards defendants from diverse cultural communities. He provides the view that “if people are going to bandy about words like equality and justice for all, they also better be prepared for those of us who are going to hold them to it.”

Through this collection of essays, the voices of Native Americans as law students, lawyers, judges, and law professors speak through storytelling and personal truths. It is hoped that the ears of the legal academy are open to hear the recommendations on incorporating Native American law, restorative justice traditions, and context for Native American legal issues into law school classrooms and curricula. The common good for law schools will be positively impacted by admitting more Native American law students and hiring more Native American law professors for a more representative, inclusive, and just legal profession.

[. . .]

Life can break you. No one can protect you from that. However, when the “system” is the wrecking ball, the breakage can become a permanent stain on your record--leading to huge implications on a person's life, finances, housing, and general reputation. This institution is supposed to protect us from that breakage when the law is not in support of the outcome. Under this same law, we all should receive equal protection. It should be ours by right. We the people, by the people, and for the people. Of course, it was never originally intended for a lot of us, and it rarely works out that way. But I'll be damned if I won't work my tail off until I see change. I mean, if people are going to bandy about words like equality and justice for all, they also better be prepared for those of us who are going to hold them to it.

Professor Angelique EagleWoman (Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate) served as the Chair of the Indian Nations and Indigenous Peoples Section of the American Association of Law Schools in 2021.

Become a Patreon!