Abstract

Excerpted From: Micah Tempel, Affirmative Action Housing: A Legal Analysis of an Ambitious but Attainable Housing Policy, 57 Real Property, Trust and Estate Law Journal 107 (Spring, 2022) (178 Footnotes) (Full Document)

The era of Jim Crow may seem a distant historical memory, but neighborhoods in the United States today are more segregated by race than they have been at any point in the last few decades. The country is becoming more and more racially diverse, but neighborhoods are growing more and more racially segregated. Residential racial segregation inflicts significant harms on all Americans and is especially detrimental for people living in segregated communities of color. Residential racial segregation is both a symptom and cause of income and wealth inequality in America. The median household income in highly segregated communities of color is approximately half of the median household income in highly segregated White neighborhoods. The median wealth of White households is almost ten times the median wealth of Black households. Although 74% of White Americans own their homes, only 45% of Black Americans are homeowners. Schools serving Black children in segregated neighborhoods have fewer resources and provide fewer opportunities than do schools serving children in predominantly White neighborhoods.

The era of Jim Crow may seem a distant historical memory, but neighborhoods in the United States today are more segregated by race than they have been at any point in the last few decades. The country is becoming more and more racially diverse, but neighborhoods are growing more and more racially segregated. Residential racial segregation inflicts significant harms on all Americans and is especially detrimental for people living in segregated communities of color. Residential racial segregation is both a symptom and cause of income and wealth inequality in America. The median household income in highly segregated communities of color is approximately half of the median household income in highly segregated White neighborhoods. The median wealth of White households is almost ten times the median wealth of Black households. Although 74% of White Americans own their homes, only 45% of Black Americans are homeowners. Schools serving Black children in segregated neighborhoods have fewer resources and provide fewer opportunities than do schools serving children in predominantly White neighborhoods.

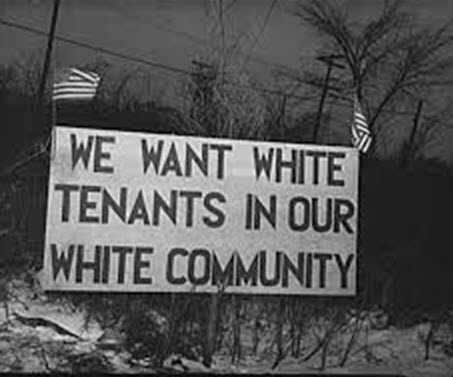

Residential racial segregation did not occur naturally as a product of private choice. Federal, state, and local governments created America's segregated neighborhoods. Between the 1930s and 1960s, governmental laws and policies across the United States mandated neighborhood racial segregation. By financing spending programs, guaranteeing loans, and broadly disseminating underwriting guidelines for home mortgage lending, the federal government incentivized the creation of exclusive, White-only neighborhoods and then channeled public benefits to residents of those neighborhoods. (In this Article, I refer to neighborhoods that had a White-only government mandate as WGM Neighborhoods.) The effects of decades of such de jure racial segregation continue today because the few legal and policy changes purportedly seeking to reverse racial segregation have been unsuccessful to integrate America's residential landscape. The federal government is responsible for creating WGM Neighborhoods and the resulting racial, social, and economic inequities that WGM Neighborhoods have created. The government is therefore constitutionally and morally required to remedy the harms resulting from its unconstitutional segregationist laws and policies.

One way in which the federal government could remedy some of the harm caused by residential racial segregation is through a federal affirmative action housing (AAH) program. One such program could empower and require the federal government to offer to purchase homes being sold in WGM Neighborhoods and then offer such homes for resale to Black Americans at a highly subsidized price, equivalent to the price Black Americans would have been able to purchase the homes for decades ago under the federal subsidy programs that previously were only available for White Americans.

Richard Rothstein proposed this general idea in his book, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. This Article will take the seed of Rothstein's idea and lay out, in more detail, what this program could actually look like. The Article will outline the contours of a possible AAH program to run it through a series of legal analyses. The purpose of the proposed program in this Article is not to assert that this is the only way to structure an AAH program, or even that it is the best way to structure it. The purpose instead is to provide enough specifics to analyze the legal hurdles that a governmental program of this nature would encounter.

Even if such an AAH program can pass legal muster, it would be unlikely to solve all the systemic racism issues that face our nation today. However, an AAH program would be one way to target one of the roots of systemic racism issues and provide meaningful economic relief to Black Americans. Federal funding and support for an AAH program would allow the government to acknowledge and to make restitution for the generational harms it caused by encouraging and propagating housing discrimination based on race.

Part I of this Article describes a possible AAH program design to analyze how such a program might be established and the legal obstacles it would face. Part II considers congressional power and authority to create an AAH program. Part III assesses whether an AAH program might be deemed unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause. Part IV examines whether an AAH program would violate the Fair Housing Act. Part V addresses likely economic and political criticisms of an AAH program. Finally, Part VI discusses possible design variations for a federal AAH program.

[. . .]

Housing in America continues to be segregated based on race. This is not the result of individual housing choices, but the result of historic and long-lasting discriminatory policies made by local, state, and federal governments. Failure to address these discriminatory housing policies has created a system where housing segregation is entrenched. Black Americans have been barred from realizing the economic and social benefits that come with owning one's own home in a neighborhood of their choice. The federal government needs to acknowledge that the few attempts to remedy housing segregation have failed. One way in which the government could do this is by enacting an AAH program. An AAH program would allow Black families to purchase homes in neighborhoods that have historically kept them out and to buy those homes at a price similar to a price which would have been paid in the 1920s and 1930s. Congress has the authority under the Thirteenth Amendment to create an AAH program, and an AAH program could be specifically tailored to comply with the Fifth Amendment. Whether or not such a program violates the Fair Housing Act as currently written, however, is more questionable, but the Act could be amended to explicitly permit an AAH program to help the government finally achieve the Act's own integration goals.

An AAH program should not be the only approach considered when contemplating redressing historic, racist housing policies. There are many other avenues than an AAH program, but an AAH program provides a very clear and direct way to begin remedying some of the harm done by the government against its own citizens. Ambitious policy ideas are often brushed aside as unworkable or too idealistic. However, it is important to take these ambitious policies and explore how they can be made to fit within our existing legal frameworks. When doing this, a bold and idealistic policy can become more grounded and attainable.

Micah Tempel, J.D. 2022, Washburn University School of Law.