Become a Patreon!

Abstract

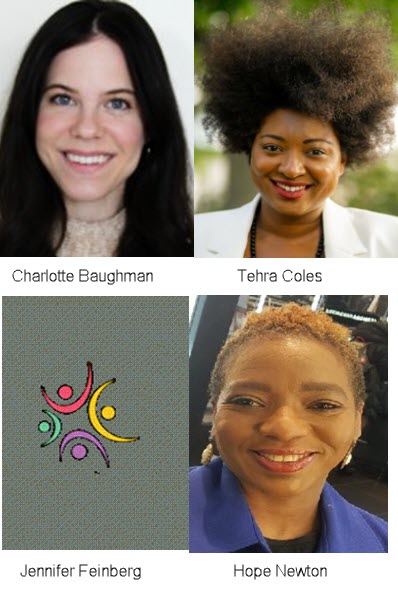

Excerpted From: Charlotte Baughman, Tehra Coles, Jennifer Feinberg and Hope Newton, The Surveillance Tentacles of the Child Welfare System, 11 Columbia Journal of Race and Law 501 (July, 2021) (82 Footnotes) (Full Document)

The child welfare system, which we refer to throughout this Article as the family regulation system, depends upon a system of surveillance to entrap low-income Black, Brown, and Native families within it. Mental health and social service providers, educational institutions, law enforcement, and the family regulation system itself, function as the surveillance tentacles of the family regulation system, drawing low-income Black and Brown families under the watchful eye and control of family regulation workers and courts. These tentacles seek out indications of neglect or abuse, which is often little more than evidence of poverty, and focus on reporting concerns and placing families under even greater levels of surveillance. By utilizing these tactics, the family regulation system causes greater trauma to impacted communities and fails to provide the support necessary to assist families living in poverty. In this Article, we explore how the family regulation system uses its surveillance tentacles to control families, without providing the assistance or protection to children it is purportedly designed to deliver. We argue that families need direct material support that is divorced from the threat of surveillance or family separation.

The child welfare system, which we refer to throughout this Article as the family regulation system, depends upon a system of surveillance to entrap low-income Black, Brown, and Native families within it. Mental health and social service providers, educational institutions, law enforcement, and the family regulation system itself, function as the surveillance tentacles of the family regulation system, drawing low-income Black and Brown families under the watchful eye and control of family regulation workers and courts. These tentacles seek out indications of neglect or abuse, which is often little more than evidence of poverty, and focus on reporting concerns and placing families under even greater levels of surveillance. By utilizing these tactics, the family regulation system causes greater trauma to impacted communities and fails to provide the support necessary to assist families living in poverty. In this Article, we explore how the family regulation system uses its surveillance tentacles to control families, without providing the assistance or protection to children it is purportedly designed to deliver. We argue that families need direct material support that is divorced from the threat of surveillance or family separation.

Mary is a 25-year-old Black mother who has been running late all week--late to pick the baby up from daycare, then late to get her to the pediatrician's office. She missed the appointment, for the third time. She was late to pick her son up from her mom's house and arrived at the shelter after curfew. Mary missed her recertification appointment at the public assistance office because her son's school bus didn't show up and she had to take him to school on public transportation. The knock on the door from the family regulation worker was the last straw. A shelter case worker overheard a heated argument between Mary and her husband and made a child maltreatment report. A family regulation worker told her that there would be a conference that same day to discuss the agency's concerns. In addition to the shelter caseworker who made the report, the family regulation worker had also talked to Mary's son's school and his pediatrician. Mary and her husband would have separate conferences because the report mentioned domestic violence. During the conference, Mary learned that a domestic violence consultant who had never met Mary or her husband had reviewed their case history and felt her children were unsafe. Mary sat at a table across from three strangers, looking down at the “service plan” and could not understand how she was going to get it all done without losing her children. The family regulation worker told her that she would have to enforce an order of protection against her husband and that he would have to find another place to live. She would be required to bring the children to the family regulation agency for supervised visits with their father, on top of enrolling in a parenting class, family therapy, domestic violence services, and complying with regular home visits from the family regulation worker. Mary could barely stay afloat, and now she was going to have to do everything on her own. She felt like she was being set up to fail, but she agreed to the plan. What other choice did she have?

There is nothing new about the policing and surveillance of Black and Brown bodies. Parents like Mary are routinely assigned “service plans” by family regulation workers as means of addressing what the latter sees as deficiencies in their parenting. These plans are rarely tailored to the needs of the family but are instead cookie cutter solutions that often make matters worse and provide a pathway for the family regulation systems to watch the family more closely and control their behavior. This control determines who is allowed to come in contact with their children, where they can live, what doctor they have to go to, what time they must be home, where and when they can work, and what services they must engage in.

Black and Brown families have been over-policed, over-surveilled, torn apart, and disrespected for hundreds of years. Black children were kidnapped and taken across the world to be enslaved. Black families were separated, and children were sold away from their parents as a means of control. Black women were considered more valuable to slave owners when they were in their “child bearing years.” Slave owners closely monitored the behavior of Black mothers to make sure that they were properly caring for their children. In the 1960s, the government sanctioned the forced removal of Native children from their families and, in most cases, placed them in white homes far from their families. By the 1970s, between “25 and 35 percent of all [Native] children had been placed in adoptive homes.” For the past several years, Brown children have been forcefully separated from their parents and detained at the border in an attempt to discourage immigration. Today, the young mothers we represent at the Center for Family Representation (CFR), who are usually Black or Brown, are frequently denied favorable settlement offers because family regulation system prosecutors believe they will have more children in the future and want to retain an easier pathway to more surveillance through subsequent court involvement that often involves micromanaging the care of their children.

The family regulation system, as the scholar Dorothy Roberts aptly describes the American child welfare system, is a continuation of this horrific American tradition. This system is perhaps one of the most glaring modern-day attempts to destroy the Black family. It is one that identifies children and families believed to be in need of intervention, largely through institutions and professionals trained to detect and mandated to report signs of child maltreatment. But these systems--like law enforcement, social services, shelters, and public schools--are entrenched in low-income communities of color by design. They identify children “at risk” for maltreatment through cross-system surveillance--the “stop and frisk” equivalent to parenting leads to a disproportionate number of Black and Brown families reported, investigated, and monitored for maltreatment.

To many, the violation of privacy and the various forms of surveillance that are forced upon low-income communities and people of color are justified as being in service of safety and support. In reality, surveillance has a negative impact on these communities. In our society, while everyone is susceptible to some level of surveillance, not everyone receives the same amount. The power of surveillance “touches everyone, but its hand is heaviest in communities already disadvantaged by their poverty, race, religion, ethnicity, and immigration status.” While privacy rights exist, people who are low-income do not have the same means to exercise them.

Organizations like CFR employ attorneys, social workers, and parent advocates to represent parents when they are targeted by the family regulation system. In New York City, where CFR is based, the family regulation system disproportionately impacts Black and Brown families for both family separation and increased surveillance. Most of the allegations our clients face are poverty-related. They are issues that could be solved with money: children left at home because a parent could not afford to pay for childcare, insufficient food in the cabinets, unstable housing, lack of medical insurance to take children to the dentist or for routine checkups, etc.

Most families that come into contact with the family regulation system cannot afford to hire an attorney or social worker to help them navigate it. Many states, like New York, do not require that family regulation workers inform parents of their rights not to speak with investigators or share information. Whenever possible, CFR tries to connect with families during the investigation stage, but these resources are not available everywhere. The family regulation system works to prevent those it seeks to surveil and control from having access to legal support. In 2018, Monroe County, New York, turned down funds that would have paid for public defense attorneys for parents. In New York City, the local family regulation system, called the Administration for Children's Services (ACS), has publicly opposed proposed city and state laws that would require parents to be informed of their rights during an investigation. Meanwhile, the family regulation system and its “surveillance tentacles” monitor families in low-income communities and increase their susceptibility to becoming entangled in the system.

This rampant surveillance is inextricably linked to mandated reporting. Laws in all fifty states enumerate which groups of people in each state are required to report suspected child abuse or maltreatment to each state's child maltreatment hotline. School personnel and teachers, mental health professionals, drug treatment counselors, law enforcement personnel, and social workers are considered mandated reporters in most states. When a state's child maltreatment hotline receives a credible report alleging child maltreatment, the local department of social services must initiate an investigation. As a result of their investigation, a family regulation worker may decide to file maltreatment allegations against a parent in court, which can in turn lead to the removal of a child or court-mandated services, or the family regulation worker may request that a parent voluntarily participate in services to avoid court involvement or a removal. Each of these results leads to more surveillance and control over Black and Brown families' daily activities. A parent targeted by the family regulation system will be under the scrutiny of various mandated reporters, from the initial reporter of the case, to the family regulation worker investigating the case, to the various service providers, mental health counselors, drug treatment providers, and social services workers the parent must interface with to apply for housing and public benefits.

Mandated reporters make approximately two-thirds of all child maltreatment reports made in the United States. The vast majority of reports to maltreatment hotlines are not substantiated. Nationally, 4.1 million cases were called into child maltreatment hotlines in 2019. Of the 4.1 million cases, 2.4 million were screened as potentially credible, with fewer than 400,000 (slightly less than 10%) determined to be credible upon further investigation. This means that millions of families are subject to an intrusive and traumatic investigation with no benefit to child safety, the purported purpose of mandated reporter laws.

Black and Brown families are disproportionately impacted by family regulation investigations. 53% of Black children living in the United States experience a family regulation investigation during their lifetime. The cumulative risk of experiencing an investigation is much higher for children living in low-income and/or non-white neighborhoods. This means that children living in low-income, non-white communities are much more likely than white children to experience multiple family regulation investigations throughout their childhood. In New York City, the rate of investigations was about four times higher in the ten districts with the highest rates of child poverty than the ten districts with the lowest child poverty rates. In districts with similar child poverty rates, districts with larger Black and Brown populations had higher rates of investigation.

[. . .]

We must reimagine the family regulation system to deliver material support to the low-income families it purportedly serves, without surveillance and prosecution. The family regulation system's dependence on surveillance and mandated reporting as a solution to child maltreatment is a fallacy. Families must have access to concrete supports and services without interacting with mandated reporters. However, any “hotline” or referral service must not be staffed by anyone connected to the family regulation system. Interventions should be informed by parents and take into account the lived experiences of the families they serve, including the impact of ongoing surveillance and systemic racism. The damage being done to Black and Brown families will continue unchecked “within all aspects of the [family regulation system] as long as we remain complicit in upholding the accepted racist conditions experienced by those most disenfranchised in our society.”

The family regulation system places a close watch on low-income Black and Brown families through the mobilization of mandated reporters, harming families and failing to produce positive outcomes for children. Provision of services and material support for the families who need it should be divorced from the family regulation system. Parents are experts on the needs of their families. They must be given the freedom to seek out necessary supportive services without fear of separation or of being subjected to a debilitating level of surveillance and control.

Until the family regulation system is dismantled, and its tentacles of surveillance amputated, Black and Brown families, especially those from low-income communities, will continue to be punished for their poverty.

Charlotte Baughman is a senior social worker, Tehra Coles and Jennifer Feinberg are litigation supervisors, and Hope Newton is a parent advocate at the Center for Family Representation (CFR).

Become a Patreon!