Abstract

Excerpted from: Curtis G. Berkey and Scott W. Williams, California Indian Tribes and the Marine Life Protection Act: The Seeds of a Partnership to Preserve Natural Resources, 43 American Indian Law Review 307 (2019) (221 Footnotes) (Full Document)

The United States Supreme Court long ago described states as the "deadliest enemies" of Indian tribes. California's relationship with the Indian tribes within its borders has too often reflected the truth of that characterization. In recent years, however, there are promising signs that California and Indian tribes have taken a new direction. If they continue on that course, the State and tribes may enjoy to their mutual benefit a new era of cooperation and collaboration, specifically with regard to the management and use of natural resources.

The United States Supreme Court long ago described states as the "deadliest enemies" of Indian tribes. California's relationship with the Indian tribes within its borders has too often reflected the truth of that characterization. In recent years, however, there are promising signs that California and Indian tribes have taken a new direction. If they continue on that course, the State and tribes may enjoy to their mutual benefit a new era of cooperation and collaboration, specifically with regard to the management and use of natural resources.

In 1999, the California Legislature enacted the Marine Life Protection Act (MLPA), which requires the State to establish an improved network of marine protected areas (MPAs) in the three-mile zone of coastal waters under state jurisdiction. MPAs are designated areas where the harvesting and gathering of marine species are regulated, and sometimes prohibited, to foster the long-term sustainability of ocean ecosystems. Like the vast majority of California laws, the MLPA did not specifically address the rights and concerns of Indian tribes even though the California coast is Indian Country for many tribes. The failure of the legislature to acknowledge the centuries-long stewardship of coastal resources by Indian people, and the commencement of a resources-protection process that did not include tribes, resulted in initial opposition from Indian tribes. Many tribes feared the process would simply be the latest in a long history of state actions that risked the extinguishment of cultural practices. Instead, despite initial misunderstandings, the MPA designation process elevated tribal engagement in-state natural resource management and may be the catalyst for a fundamental shift in California's approach to tribal nations.

This Article describes tribal engagement in California's MPA planning process, its outcome, and the extent to which the result sparked changes in state-tribal cooperation in other areas of natural resource policy.

The Article has seven parts:

1) a brief historical overview of California's treatment of Indian tribes;

2) the development of the Marine Life Protection Act;

3) the experience of the Kashia Band of Pomo, which encountered the State's unilateral imposition of a resource protection zone on a tribal traditional spiritual area;

4) the legal backdrop of California Indian tribes' rights to off-reservation subsistence marine resources;

5) the process on the North Coast of developing a tribal marine resource use regulation;

6) the role of Indian tribes in the implementation of the MPA network and species protections; and

7) the implications of the MLPA outcome for California and tribal relations beyond the MLPA.

[. . .]

The tribal-state collaboration produced benefits for both governments in establishing a workable policy to restore and protect marine resources while simultaneously preserving the traditional practices of the Indian tribes. The various ways in which these changes will be realized depend on the political will of these sovereign governments to continue this partnership and incorporate its benefits into other public policy areas. In the natural resources arena, the Governor, the Secretary, and the Fish and Game Commission set the policy; it is implemented at the departmental level. It is at the departmental level that the functional decisions are made: authority is granted for projects, permits are issued for activities, and the relationship is implemented. The obligations imposed on state agencies to collaborate with tribes are now embedded at the departmental level, at least with respect to natural resources. California now "does business," as Governor Babbitt may have said, with tribes at the functional level. That may provide reason to believe that, as the political pendulum swings with successor State Administrations, the value of tribal/state collaboration will continue and the benefits to both will be fully realized.

From the tribal perspective, it seems unlikely that Indian nations would easily give up the recognition of rights they have achieved through collaboration. The process from the Kashia's Stewarts Point Marine Reserve in 2009, when Indian interests were not initially considered, to the North Coast Marine Protection Areas in 2012 when the tribes' right to take resources sustainably was recognized, was arduous. The disagreements and compromises, however, fostered mutual respect. And the process, to use Director Bonham's word, is now "embedded" in the State's administrative apparatus. It is entirely possible that a long, frustrating, yet successful process is more likely to last and to become a foundation for future partnerships.

There is much more that could be achieved by a state that has the largest number of Indian tribes and native people in the Nation, including: legislative committees devoted specifically to Indian affairs; a state commission on Indian affairs; increased representation in the Legislature for Indian tribes; formal acknowledgement of, and reparations for, state-sanctioned violence that decimated Indian tribes for generations; and educating all three branches of state government about the historic and current struggles of tribal communities. The MLPAI laid a strong foundation for these and other changes that could mark a new day in the relationship between Indian tribes and California. In the end, it turned out that the MLPAI was about more than marine resources.

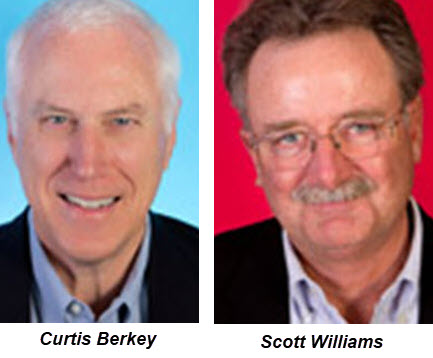

Curtis G. Berkey is Partner, Berkey Williams LLP.

Scott W. Williams is Partner, Berkey Williams LLP.

Please visit my Patreon Page