Become a Patreon!

Abstract

Excerpted From: Lizette Rodriguez, Stop Punishing Our Kids: How Title VII Can Protect Children of Color in Public School's Discipline Practices, 39 Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary 19 (Spring, 2020) (257 Footnotes) (Full Document)

From Trayvon Martin to Stephan Clark, news headlines plague the United States to constantly remind Americans that colored children do not get the benefit of the doubt in encounters with authority figures--that somehow a person's skin color skin influences the probability of his culpability. In fact, after analyzing available FBI data, reporter Dara Lind found that “[American] police kill black people at disproportionate rates: [b]lack people accounted for 31% of police killing victims in 2012" while they only accounted for 13% of the American population. Moreover, a Guardian study of police killings in 2015 found that racial minorities constitute 46.6% of the American population, but represented 62.7% of unarmed people police killed. After the killings of several unarmed black men, the “Black Lives Matter” movement took shape to “build local power and to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes.”

From Trayvon Martin to Stephan Clark, news headlines plague the United States to constantly remind Americans that colored children do not get the benefit of the doubt in encounters with authority figures--that somehow a person's skin color skin influences the probability of his culpability. In fact, after analyzing available FBI data, reporter Dara Lind found that “[American] police kill black people at disproportionate rates: [b]lack people accounted for 31% of police killing victims in 2012" while they only accounted for 13% of the American population. Moreover, a Guardian study of police killings in 2015 found that racial minorities constitute 46.6% of the American population, but represented 62.7% of unarmed people police killed. After the killings of several unarmed black men, the “Black Lives Matter” movement took shape to “build local power and to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes.”

As crucial as it is to bring attention to these incidents and demand change, it is almost equally important to dig deeper into the issue and see that students of color are being disproportionately punished in the classroom as well. It is a gross over-simplification to presume that the racial disparity in public school discipline trends is a result of students of color simply being more troublesome. However, calling it discrimination does not make it so. In the legal realm, there is a remedy for discrimination. Traditionally, to establish that someone has engaged in discriminatory practices, the accuser must demonstrate that the person intended to be discriminatory. This article will discuss this notion in detail.

According to the Equal Protection Clause, to pursue a legal remedy for this prominent racial disparity in school discipline, the plaintiff must be able to show that the school officials intended to discriminate against students of color. In this day and age, people are not openly declaring that their actions are a result of racial discrimination, making this a difficult standard to meet. Therefore, this article attempts to distinguish what legal remedies are available to the children affected and what the Department of Education can do to address the issues that the law cannot.

Section I considers the evolution of education in the United States and how American society dealt with racial discrimination in public schools in the past, and how those facts and decisions differ from the issues that students of color are facing today. Section II explains the Equal Protection Clause (EPC) and analyzes the seminal cases that demonstrate the power of the EPC and when it is appropriate to use it. Section III introduces Title VII and walks through violations of disparate impact discrimination and disparate treatment discrimination. Section IV explains what the Department of Education's Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) is and what the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GOA) found after analyzing the 2013 and 2014 data on public school discipline across the country. Section V analyzes the GOA study facts with the legal standards of the EPC and Title VII to consider if Black students had a legal remedy under the current laws. Section VI uses Title VII as a template for new legislation that can better protect students against the current trends of public-school discipline. Section VII considers what current state of the country in regard to education and racial tensions more broadly and how Congress must react shift the current trends.</p

[. . .]

The Equal Protection Clause is a constitutional right all citizens have to the equal protection of the law. However, equal protection of the law does not guarantee equal results, and unequal results do not signify discrimination. Consequently, for a person that suffered from the disproportionate impact of the law to claim that it violated her EPC right, she must show it was intentional discrimination. She must prove that the man behind the curtain intended to discriminate against their protected trait. However, the difficulty of the EPC is that it is hard to prove a person's state of mind.

The legislature passed a positive law, Title VII, which ensures that job applicants have an equal opportunity to employment. Congress and the courts recognized that discrimination could occur without anyone intending it to and included the disparate impact provision as an avenue to a legal remedy. This opened the door to alleviating discrimination in ways that the EPC could not, Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary 39-2 because it no longer required the plaintiff to prove thoughts, only results.

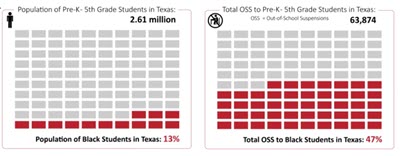

The CRDC and GAO studies provided results that some people knew--that schools discipline black children at statistically disproportionate rates in public schools. The GAO numbers do not lie. There can be alternative reasoning, but the numbers show that there is a problem--and it is discrimination. Unfortunately, under the EPC looking like discrimination is not enough to seek a legal remedy. However, school discipline is an aspect of education that permeates the student's life inside and outside of the classroom. It is important to question why black children experience more discipline, instead of assuming they are more disobedient. Such an assumption would only protect a racial status quo this country has striven to dismantle for the past fifty-years.

It is time for Congress to rise and create positive law that protects the children of this country in areas that the drafters of the Constitution did not consider. It is time for Title E.

Lizette Rodriguez is a third-year law student at Pepperdine University School of Law.

Become a Patreon!