Become a Patreon!

Abstract

Excerpted From: Harvey Gee, Surveillance State: Fourth Amendment Law, Big Data Policing, and Facial Recognition Technology, 21 Berkeley Journal of African-American Law & Policy 43 (2021) (342 Footnotes) (Full Document) (Book Review: The Rise of Big Data Policing: Surveillance, Race, and the Future of Law Enforcement. Andrew Guthrie Ferguson. New York University Press, 2017. Pp.259. $28.00 Smart Surveillance: How to Interpret the Fourth Amendment in the Twenty-First Century. Ric Simmons. Cambridge University Press, 2019. Pp.264. $34.99 )

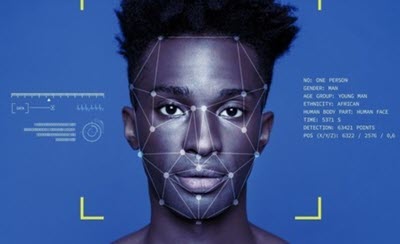

The surveillance state is here. Law enforcement in major cities used surveillance technology to watch and track protesters in the mass protests over the deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, and other young African Americans. The Department of Homeland Security monitored and tracked Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in more than 15 cities using military-grade technology, including infrared and electro-optical cameras and “dirty box” devices on airplanes, drones, and helicopters. On the ground, the San Francisco Police Department conducted real-time mass video surveillance of BLM protesters despite a citywide ban on such conduct. Such digital spying is not new. For the past decade, police departments across the country, in an effort to reduce gun violence, have been using ShotSpotter gunshot technology in minority communities to track the sound of gunshots. In 2014, Stingrays were used as spying tools by local police departments during demonstrations. And despite initial denials, the Los Angeles Police Department admitted to using facial recognition nearly 30,000 times since 2009.

The surveillance state is here. Law enforcement in major cities used surveillance technology to watch and track protesters in the mass protests over the deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, and other young African Americans. The Department of Homeland Security monitored and tracked Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in more than 15 cities using military-grade technology, including infrared and electro-optical cameras and “dirty box” devices on airplanes, drones, and helicopters. On the ground, the San Francisco Police Department conducted real-time mass video surveillance of BLM protesters despite a citywide ban on such conduct. Such digital spying is not new. For the past decade, police departments across the country, in an effort to reduce gun violence, have been using ShotSpotter gunshot technology in minority communities to track the sound of gunshots. In 2014, Stingrays were used as spying tools by local police departments during demonstrations. And despite initial denials, the Los Angeles Police Department admitted to using facial recognition nearly 30,000 times since 2009.

Do Fourth Amendment protections even exist in such public forums? Who decides the limits and efficacy of the police use of mass-surveillance technologies to monitor peaceful protests? Will the police continue to use these new technologies to disproportionately target racial minorities? Two books written by Fourth Amendment scholars attempt to unpack these questions. Readers in the pro-privacy rights and racial justice camps will resonate with Andrew Guthrie Ferguson in The Rise of Big Data Policing: Surveillance, Race, and the Future of Law Enforcement. Whereas readers who favor police using more law enforcement surveillance and investigation, and who disagree with the Supreme Court's recent Fourth Amendment technology rulings upholding the constitutional right to be protected from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government, will find Ric Simmons's Smart Surveillance: How to Interpret the Fourth Amendment in the Twenty-First Century more appealing.

Both books are persuasive and insightful. Rise of Big Data Policing and Smart Surveillance certainly add to the growing Fourth Amendment scholarship analyzing the impact of emerging surveillance technology on privacy. Ferguson weighs the pros and cons of surveillance technology, and then dives deeper into its impact on racial communities. Rise of Big Data Policing consists of ten descriptive and prescriptive chapters covering the rise of data surveillance and data-driven policing, addressing the important questions of whom, where, when, and how we police. In contrast, Smart Surveillance enthusiastically embraces the view that more technology surveillance is needed because it can prevent crime, help catch criminals, monitor police, and reduce racial profiling. The eight chapters offer a cost-benefit analysis of surveillance and demonstrate how to measure the benefits of public surveillance, big data policing, and mosaic searches. The chapters conclude with a discussion of the third-party doctrine and hyper-intrusive searches. Both books are timely, clearly written, and thoroughly researched.

This Review uses the dominant themes presented in Rise of Big Data Policing and Smart Surveillance to argue that the benefits of having public surveillance are significantly outweighed by the government's abuse of surveillance technology and the corresponding reduction in our reasonable expectation of privacy. Part One analyzes the primary arguments presented in Rise of Big Data Policing. Part Two considers the key arguments presented in Smart Surveillance. Part Three examines recent developments in surveillance technology and Fourth Amendment jurisprudence that have occurred since the release of the two volumes. This section builds on the substantive background provided by Ferguson and Simmons to extend the conversation about the inherent tensions between emerging surveillance and Fourth Amendment jurisprudence. Part Three focuses on some of the most popular and powerful surveillance tools used by local police departments with little oversight: pole cameras, Stingray cell-site simulators, and facial recognition and surveillance technology. These newer technologies purportedly help police fight crime, but they can also potentially infringe on privacy rights.

[. . .]

As companion books, Rise of Big Data Policing and Smart Surveillance engage in an important dialogue about the growth of new technologies and how citizens, legislators, the police, and the court system need to work together to advance Fourth Amendment jurisprudence so that our civil liberties are protected. As this Review has vividly shown, the benefits of having public surveillance are significantly outweighed by the government's abuse of surveillance technology and the corresponding reduction in our reasonable expectation of privacy under the Fourth Amendment. As the national conversation about racial justice continues, more accountability and transparency on the part of the police, the courts, and legislators are desperately needed. States and cities should continue to pass laws that require regulation of police acquisition and the use of surveillance technology. The surveillance state is here.

The author is an attorney in San Francisco. He previously served as an attorney with the Office of the Federal Public Defender in Las Vegas and Pittsburgh, the Federal Defenders of the Middle District of Georgia, and the Office of the Colorado State Public Defender. B.A., Sonoma State University; J.D., St. Mary's School of Law; LL.M., The George Washington Law School.

Become a Patreon!